Error Culture Part III

How can I tell if I'm in an error culture?

In part 1 I spoke about the idea of Error Culture. In that post I define what error culture.

In part 2 I spoke when Error Culture starts. This time I'll talk about how you can tell if you're living in an Error Culture, and what you can do about it.

Below are a couple of tell-tale signs I've found to determine if you're living in an error culture.

Email Rules

You start your day and fire up your email client. As the application opens up you see the number of unread message go from 500 down to 20. You think back to a time when you would open your email client and have to trod through ALL 500 of those emails. Now though ... now you've outsmarted the email system by implementing several rules to ignore or hide those pesky emails that don't seem to mean anything.

Instinct to just delete emails

Maybe you don't know about the amazing opportunities that email client rules offer, so you start going through your emails. You delete the ones you know aren't useful or don't mean anything.

Or maybe you do know about rules and of the remaining 20 you notice a few new emails that you don't need to act on. Your first instinct is to delete them, but you remember you are a smart email user and create a new rule to get rid of those emails as well.

Why do I get this email anyway?

If you use rules, you recall a time before you had them. A time when you would methodically read each email and write down a quick note to ask a co-worker, or your boss at your next one on one. But when you brought up the alerts you had one of two reactions:

- Oh those ... yeah, you can just delete them. They don't mean anything

- Ugh ... how do you not know what that is for? Fine, let me explain it to you ... again

The first item is definitely error culture. The second response could be error culture if the person you've asked is just so overwhelmed with all of the alerts ... OR it could just be a toxic culture. If it's a toxic culture, I'm sorry, but this post might not be helpful in solving that problem.

If you're not in the second situation you may (rightfully) ask

why do we get it if we can just delete it?

And if the answer is 🤷♂️ then you might be in an error culture.

In general, if no one knows WHY we're getting an email and there is no actionable direction, you might be in an error culture.

Email Alerts

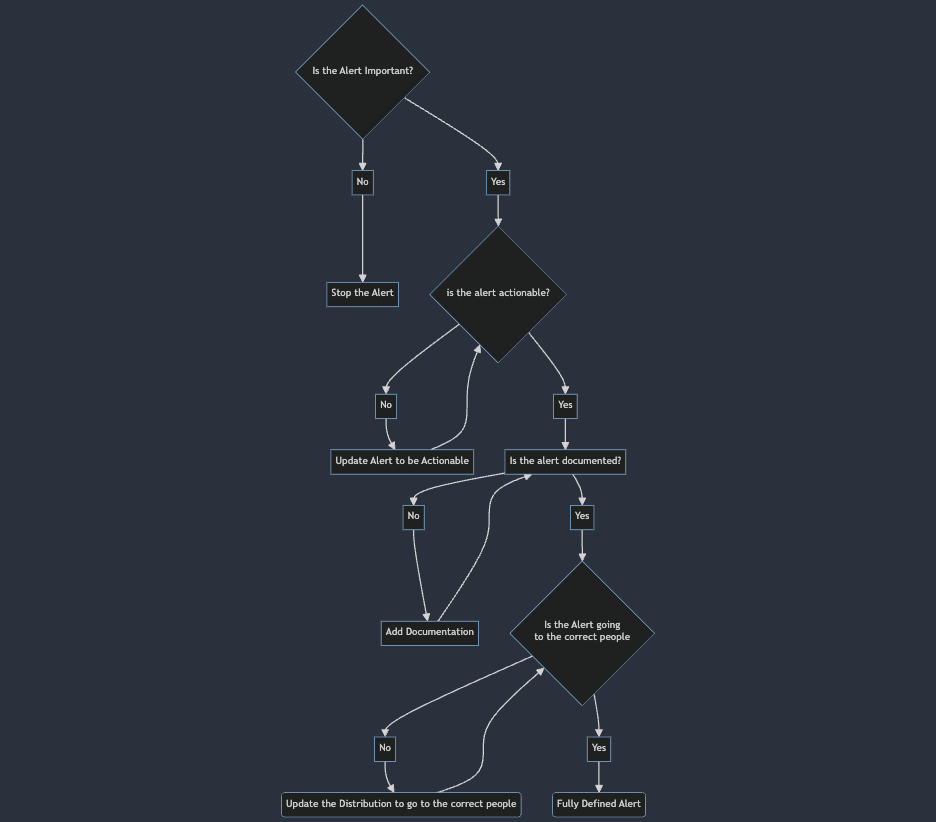

Ask yourself, your peers, and your boss this question

Is this alert we are getting actually important?

If the answer is No, then delete the mechanism that generates the error. Don't just create a rule to delete the alert.

If the answer is Yes, then ask

Is the alert you are getting actionable?

If the answer is No then update the alert to be actionable. This can be done by

- Including steps to resolution or documentation link for resolving the error

- Update the alert to indicate it’s importance

- Update the alert to go to the correct people

If the answer is Yes then

- Make sure the error indicates what the fix needs to be

- Make sure the error indicates why it’s important, or a link to documentation that explains it

- Make sure the right people are being notified

Point three here is really important. To determine if the correct people are being notified ask this questions of EVERYONE that receives the alert:

Are you the correct person to do something to fix the error

If the answer is No then getting removed from the email is the best course of action.

Of course, it could be that no one ever told you why you were getting the alert so the decision to remove people from alerts may need to be a management level decision, but it can at least start the conversation.

If the answer is Yes then do you (i.e. the person being asked) know what to do to fix the error

Again, with a simple yes or no response, you have two options:

Yes: Does the error indicate what the fix needs to be or where to go to find out? No: Work to update the error to make it actionable

This can help to get the right people getting the alerts.

Below is a flow chart to help make alerts better

None of this is easy to change. You may have managers that don't answer your questions when asking about if someone should receive an alert.

You may not get feedback from your peers, or manager about cleaning up the alert system. But if you can become a champion for the effort it will be very helpful for everyone involved.

If you implement something like this you can increase the signal to noise ratio for you and your team. That seems like a big win for everyone.

Error Culture Part II

In my last post I spoke about the idea of Error Culture. In that post I define what error culture. This time I'll talk about when it starts to happen. For a recap go back and read that before diving in here.

When does error culture start?

Error culture can start because of internal reason, external reason, or both and are almost always driven by the best of intentions. Error culture starts to happen because we don't finish the alert process. That is, we set up the alerts, but we don't indicate why they are important or what to do about them when we're notified.

Internal

Internal pressures driving error culture can usually be traced back to someone (usually someone important 1) declaring that ‘we’ need to be notified of when ‘this’ happens again. In and of itself self, this is actually a really good idea.

But if the important person doesn't identify why we need to be notified all that happens is that an alert is set up and NO ONE knows what to do when it fires off.

The opposite side of the coin here is being proactive in wanting to be notified when a bad thing might happen and being notified might be useful. Again, if there is no definition for why the alert might be useful, you're simply creating noise and encouraging alerts to be ignored.

External

External pressures that can drive error culture are similar to internal ones. There are some slight differences though.

For example, a consultant might indicate that it is best practice TM to be notified of an alert. However, they don't provide more context for why it's best practice. It could very well be that the recommendation IS best practice, but for a user base that is 100x your user base, or for an organization that is 1/10th your size. Context matters and while best practices should scale, they don't always.

Another example of external drivers are software applications provided by third party vendors with default alerts enabled but no context or steps for resolution. Sometimes there will be documentation describing the alert process, but without the context for why the alert is important it's just as likely to be ignored.

So far in this series we've seen what error culture is,and when it starts to happen. In the next post I'll talk about how to identify if you're in an error culture.

- important here just means someone with influence ↩︎

Error Culture

What is Error Culture?

It's inevitable that at some point a service 1 will fail. When that service fails you can either choose to be alerted, or not. Because technology is so important to so many aspects of work, not getting an alert for a failing service isn't really an option. So we enable alerts ... for EVERYTHING.

This is good in that we know when things have gone bad ... but it's bad in that we can start to ignore these alerts because we get false positives. If you hear comments like,

Oh yeah, that error always comes up, but we just ignore it because it doesn't mean anything

or

We don't really know why that error occurs, but it doesn't seem to impact anything, so we just ignore it

This is what I am calling, "Error Culture".

OK, but why is that bad?

Initially, it might not feel bad.

EVERYONE knows that you can ignore that error because it doesn't mean anything. Of course, this knowledge tends to NOT be documented anywhere, so when you onboard new team members they don't know what EVERYONE knows ... because they weren't part of the EVERYONE that learned the lesson.

Additionally, if you're getting error messages and nothing truly bad every happens, then a few things can happen:

- People start to question ALL of the alerts. I mean, if this one isn't valid, why is this OTHER one valid? Maybe I can ignore both 🤷♂️

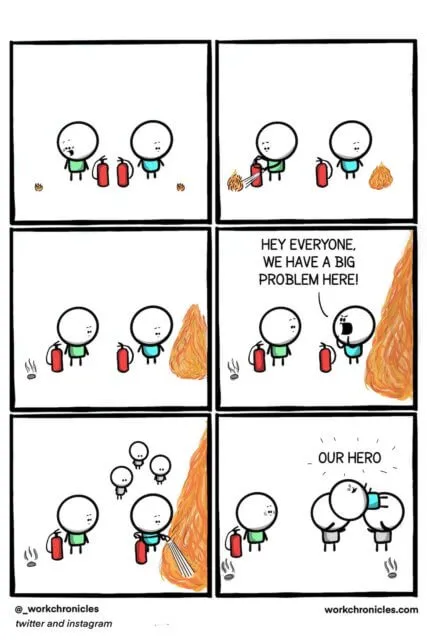

- You may be getting an alert about a small thing that can be ignored until it's a BIG thing. I think this image does good job of illustrating the point (found here)

Why does it happen?

In general, I've found that error culture can happen for a few reason

Error Fatigue

If you get 1000 alerts every day, you're not going to be able to do anything about anything. This is similar phenomenon to 'Alert Fatgiue' which can happen in software applications (my experience is in Electronic Health Record systems) where users can just click OK or Cancel when an alert shows up and users may not actually see that there is a problem

Lack of understanding of what the error is

It's surprising to find that people that receive alerts and they just delete them. They do this not out malice, but because they honeslty do not know what the alert is for. They were maybe opted into the alert (with no way to opt out) and therefore have no idea why they get it or what they are supposed to do with it. They may also be in an organization where asking questions to learn isn't encouraged and will therefore not ask why they are getting the alert.

Lack of understanding of why the error is important

Related to the item above, but different, a person can receive an alert, but they don't understand why it's important. This is usually manifested in some of the things mentioned before. Ideas like,

well, I've ignored this alert every day for 6 months, I don't know why I need to do anything about it now!

Lack of understand of who the error will impact

I'm reminded of the Episode of Friends where there is a light switch in Chandler and Joey's apartment and they don't know what it's for. At the end of the episide Monica is idly flipping the switch off and on and the camera pans to a Monica and Rachel's apartment where their TV keeps turning off and on.

Error culture can have a similar feeling. If I get an error every few days, but it doesn't impact me or my work I am likely to ignore it. It could be that the error is unimporatnt for me, but HUGELY important for you. This is a case where the error is being directled incorrectly. If we both got the error you could see that I got the email and then ask, hey, are you going to do anything about this?

Emphasis on Hero Culture

This is probably the worst of all possibilities. Some cultures tend to emphasize Heroes or White Knights. They appreciate when someone comes in and 'Saves the Day'. Sometimes people get promoted because of this.

This tends to disincentivize the idea of fixing small problems before they become BIG problems. I might be getting an alert about an issue, but it's not a BIG deal and won't be for some time. Once it becomes a big deal I'll know how to fix it quickly, and I will. When I do, I'll be celebrated. Who wouldn't want that?

In this post I've identified some of the characteristics of Error Culture.

In the next post I'll talk about how to tell if you're in an Error Culture.

In the final post I'll write about what you might be able to do to mitigate, and maybe even eliminate, Error Culture where you are.

- When I say service here I mean very loosely anything from a micro service up to a physical server. ↩︎