Using PostgreSQL

Once you’ve deployed your code to a web server, you’ll be pretty stoked. I know I was. One thing you’ll need to start thinking about though is converting your SQLite database to a ‘real’ database. I say ‘real’ because SQLite is a great engine to start off with, but once you have more than 1 user, you’ll really need to have a database that can support concurrency, and can scale when you need it to.

Enter PostgreSQL. Django offers built-in database support for several different databases, but Postgres is the preferred engine.

We’ll take care of this in stages:

- Create the database

- Prep project for use of Postgres

- Install needed package

- Update

settings.pyto change to Postgres - Run the migration locally

- Deploy updates to server

- Script it all out

Create the database

I’m going to assume that you already have Postgres installed locally. If you don’t, there are many good tutorials to walk you through it.

You’ll need three things to create a database in Postgres

- Database name

- Database user

- Database password for your user

For this example, I’ll be as generic as possible and choose the following:

- Database name will be

my_database - Database user will be

my_database_user - Database password will be

my_database_user_password

From our terminal we’ll run a couple of commands:

# This will open the Postgres Shell

psql

# From the psql shell

CREATE DATABASE my_database;

CREATE USER my_database_user WITH PASSWORD 'my_database_user_password';

ALTER ROLE my_database_user SET client_encoding TO 'utf8';

ALTER ROLE my_database_user SET default_transaction_isolation TO 'read committed';

ALTER ROLE my_database_user SET timezone TO 'UTC'

The last 3 ALTER commands are based on Django recommendations for Postgres user.

One thing to note, before you go creating databases and users, you should make sure that they don’t already exist. The \l will list the various databases present. If this is your first time in the psql shell you’ll see three databases list:

postgres

template0

template1

To see a list of the users \du will display that. If this is your first time in the psql shell you’ll see one user listed:

postgres

OK … the database has been created. Next, we start updating our project to use this new database engine

Prep project for use of Postgres

Install Needed Package

The only python package needed to use Postgres is psycopg2-binary so we’ll

pip install psycopg2-binary

Update settings.py

The DATABASES portion of the settings.py is set to use SQLite by default and will look (something) like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3',

'NAME': 'mydatabase',

}

}

The Django documentation is really good on what changes need to be made. From the documentation we see that we need to update the DATABASES section to be something like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.postgresql',

'NAME': 'mydatabase',

'USER': 'mydatabaseuser',

'PASSWORD': 'mypassword',

'HOST': '127.0.0.1',

'PORT': '5432',

}

}

With our database from above, ours will look like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.postgresql',

'NAME': 'my_database',

'USER': 'my_database_user',

'PASSWORD': 'my_database_user_password',

'HOST': 'localhost',

'PORT': '',

}

}

The HOST is changed to localhost and we remove the value for PORT

Once we get ready to push this to our web server we’ll want to replace the NAME, USER, and PASSWORD with environment variables, but we’ll get to that later

Run migrations

OK, we’ve got our database set up, we’ve got our settings updated to use the new database, now we can run set that database up.

All that we need to do is to:

python manage.py migrate

This will run any migrations that we had created previously on our new Postgres database.

A few things to note:

- You will need to create a new

superuser - You will need to migrate over any data from the old SQLite database1

Congratulations! You’ve migrated from SQLite to Postgres!

- This can be done with the

datadumpanddataloadcommands available inmanage.py↩︎

Automating the deployment

We got everything set up, and now we want to automate the deployment.

Why would we want to do this you ask? Let’s say that you’ve decided that you need to set up a test version of your site (what some might call UAT) on a new server (at some point I’ll write something up about about multiple Django Sites on the same server and part of this will still apply then). How can you do it?

Well you’ll want to write yourself some scripts!

I have a mix of Python and Shell scripts set up to do this. They are a bit piece meal, but they also allow me to run specific parts of the process without having to try and execute a script with ‘commented’ out pieces.

Python Scripts

create_server.py

destroy_droplet.py

Shell Scripts

copy_for_deploy.sh

create_db.sh

create_server.sh

deploy.sh

deploy_env_variables.sh

install-code.sh

setup-server.sh

setup_nginx.sh

setup_ssl.sh

super.sh

upload-code.sh

The Python script create_server.py looks like this:

# create_server.py

import requests

import os

from collections import namedtuple

from operator import attrgetter

from time import sleep

Server = namedtuple('Server', 'created ip_address name')

doat = os.environ['DIGITAL_OCEAN_ACCESS_TOKEN']

# Create Droplet

headers = {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

'Authorization': f'Bearer {doat}',

}

data = <data_keys>

print('>>> Creating Server')

requests.post('https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets', headers=headers, data=data)

print('>>> Server Created')

print('>>> Waiting for Server Stand up')

sleep(90)

print('>>> Getting Droplet Data')

params = (

('page', '1'),

('per_page', '10'),

)

get_droplets = requests.get('https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets', headers=headers, params=params)

server_list = []

for d in get_droplets.json()['droplets']:

server_list.append(Server(d['created_at'], d['networks']['v4'][0]['ip_address'], d['name']))

server_list = sorted(server_list, key=attrgetter('created'), reverse=True)

server_ip_address = server_list[0].ip_address

db_name = os.environ['DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME']

db_username = os.environ['DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME']

if server_ip_address != <production_server_id>:

print('>>> Run server setup')

os.system(f'./setup-server.sh {server_ip_address} {db_name} {db_username}')

print(f'>>> Server setup complete. You need to add {server_ip_address} to the ALLOWED_HOSTS section of your settings.py file ')

else:

print('WARNING: Running Server set up will destroy your current production server. Aborting process')

Earlier I said that I liked Digital Ocean because of it’s nice API for interacting with it’s servers (i.e. Droplets). Here we start to see some.

The First part of the script uses my Digital Ocean Token and some input parameters to create a Droplet via the Command Line. The sleep(90) allows the process to complete before I try and get the IP address. Ninety seconds is a bit longer than is needed, but I figure, better safe than sorry … I’m sure that there’s a way to call to DO and ask if the just created droplet has an IP address, but I haven’t figured it out yet.

After we create the droplet AND is has an IP address, we get it to pass to the bash script server-setup.sh.

# server-setup.sh

#!/bin/bash

# Create the server on Digital Ocean

export SERVER=$1

# Take secret key as 2nd argument

if [[ -z "$1" ]]

then

echo "ERROR: No value set for server ip address1"

exit 1

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Setting up $SERVER"

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Updating apt sources"

apt-get -qq update

echo -e "\n>>> Upgrading apt packages"

apt-get -qq upgrade

echo -e "\n>>> Installing apt packages"

apt-get -qq install python3 python3-pip python3-venv tree supervisor postgresql postgresql-contrib nginx

echo -e "\n>>> Create User to Run Web App"

if getent passwd burningfiddle

then

echo ">>> User already present"

else

adduser --disabled-password --gecos "" burningfiddle

echo -e "\n>>> Add newly created user to www-data"

adduser burningfiddle www-data

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Make directory for code to be deployed to"

if [[ ! -d "/home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle" ]]

then

mkdir /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle

else

echo ">>> Skipping Deploy Folder creation - already present"

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Create VirtualEnv in this directory"

if [[ ! -d "/home/burningfiddle/venv" ]]

then

python3 -m venv /home/burningfiddle/venv

else

echo ">>> Skipping virtualenv creation - already present"

fi

# I don't think i need this anymore

echo ">>> Start and Enable gunicorn"

systemctl start gunicorn.socket

systemctl enable gunicorn.socket

EOF

./setup_nginx.sh $SERVER

./deploy_env_variables.sh $SERVER

./deploy.sh $SERVER

All of that stuff we did before, logging into the server and running commands, we’re now doing via a script. What the above does is attempt to keep the server in an idempotent state (that is to say you can run it as many times as you want and you don’t get weird artifacts … if you’re a math nerd you may have heard idempotent in Linear Algebra to describe the multiplication of a matrix by itself and returning the original matrix … same idea here!)

The one thing that is new here is the part

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

...

EOF

A block like that says, “take everything in between EOF and run it on the server I just ssh’d into using bash.

At the end we run 3 shell scripts:

setup_nginx.shdeploy_env_variables.shdeploy.sh

Let’s review these scripts

The script setup_nginx.sh copies several files needed for the nginx service:

gunicorn.servicegunicorn.socketsnginx.conf

It then sets up a link between the available-sites and enabled-sites for nginx and finally restarts nginx

# setup_nginx.sh

export SERVER=$1

export sitename=burningfiddle

scp -r ../config/gunicorn.service root@$SERVER:/etc/systemd/system/

scp -r ../config/gunicorn.socket root@$SERVER:/etc/systemd/system/

scp -r ../config/nginx.conf root@$SERVER:/etc/nginx/sites-available/$sitename

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

echo -e ">>> Set up site to be linked in Nginx"

ln -s /etc/nginx/sites-available/$sitename /etc/nginx/sites-enabled

echo -e ">>> Restart Nginx"

systemctl restart nginx

echo -e ">>> Allow Nginx Full access"

ufw allow 'Nginx Full'

EOF

The script deploy_env_variables.sh copies environment variables. There are packages (and other methods) that help to manage environment variables better than this, and that is one of the enhancements I’ll be looking at.

This script captures the values of various environment variables (one at a time) and then passes them through to the server. It then checks to see if these environment variables exist on the server and will place them in the /etc/environment file

export SERVER=$1

DJANGO_SECRET_KEY=printenv | grep DJANGO_SECRET_KEY

DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD=printenv | grep DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD

DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME=printenv | grep DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME

DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME=printenv | grep DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME

DJANGO_SUPERUSER_PASSWORD=printenv | grep DJANGO_SUPERUSER_PASSWORD

DJANGO_DEBUG=False

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

if [[ "\$DJANGO_SECRET_KEY" != "$DJANGO_SECRET_KEY" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_SECRET_KEY=$DJANGO_SECRET_KEY" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_SECRET_KEY - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD" != "$DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD=$DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME" != "$DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME=$DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME" != "$DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME=$DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_DEBUG" != "$DJANGO_DEBUG" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_DEBUG=$DJANGO_DEBUG" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_DEBUG - already present"

fi

EOF

The deploy.sh calls two scripts itself:

# deploy.sh

#!/bin/bash

set -e

# Deploy Django project.

export SERVER=$1

#./scripts/backup-database.sh

./upload-code.sh

./install-code.sh

The final two scripts!

The upload-code.sh script uploads the files to the deploy folder of the server while the install-code.sh script move all of the files to where then need to be on the server and restart any services.

# upload-code.sh

#!/bin/bash

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Copying Django project files to server."

if [[ -z "$SERVER" ]]

then

echo "ERROR: No value set for SERVER."

exit 1

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Preparing scripts locally."

rm -rf ../../deploy/*

rsync -rv --exclude 'htmlcov' --exclude 'venv' --exclude '*__pycache__*' --exclude '*staticfiles*' --exclude '*.pyc' ../../BurningFiddle/* ../../deploy

echo -e "\n>>> Copying files to the server."

ssh root@$SERVER "rm -rf /root/deploy/"

scp -r ../../deploy root@$SERVER:/root/

echo -e "\n>>> Finished copying Django project files to server."

And finally,

# install-code.sh

#!/bin/bash

# Install Django app on server.

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Installing Django project on server."

if [[ -z "$SERVER" ]]

then

echo "ERROR: No value set for SERVER."

exit 1

fi

echo $SERVER

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Activate the Virtual Environment"

source /home/burningfiddle/venv/bin/activate

cd /home/burningfiddle/

echo -e "\n>>> Deleting old files"

rm -rf /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle

echo -e "\n>>> Copying new files"

cp -r /root/deploy/ /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle

echo -e "\n>>> Installing Python packages"

pip install -r /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/requirements.txt

echo -e "\n>>> Running Django migrations"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py migrate

echo -e "\n>>> Creating Superuser"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py createsuperuser --noinput --username bfadmin --email rcheley@gmail.com || true

echo -e "\n>>> Load Initial Data"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py loaddata /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/fixtures/pages.json

echo -e "\n>>> Collecting static files"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py collectstatic

echo -e "\n>>> Reloading Gunicorn"

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart gunicorn

EOF

echo -e "\n>>> Finished installing Django project on server."

Preparing the code for deployment to Digital Ocean

OK, we’ve got our server ready for our Django App. We set up Gunicorn and Nginx. We created the user which will run our app and set up all of the folders that will be needed.

Now, we work on deploying the code!

Deploying the Code

There are 3 parts for deploying our code:

- Collect Locally

- Copy to Server

- Place in correct directory

Why don’t we just copy to the spot on the server we want o finally be in? Because we’ll need to restart Nginx once we’re fully deployed and it’s easier to have that done in 2 steps than in 1.

Collect the Code Locally

My project is structured such that there is a deploy folder which is on the Same Level as my Django Project Folder. That is to say

We want to clear out any old code. To do this we run from the same level that the Django Project Folder is in

rm -rf deploy/*

This will remove ALL of the files and folders that were present. Next, we want to copy the data from the yoursite folder to the deploy folder:

rsync -rv --exclude 'htmlcov' --exclude 'venv' --exclude '*__pycache__*' --exclude '*staticfiles*' --exclude '*.pyc' yoursite/* deploy

Again, running this form the same folder. I’m using rsync here as it has a really good API for allowing me to exclude items (I’m sure the above could be done better with a mix of Regular Expressions, but this gets the jobs done)

Copy to the Server

We have the files collected, now we need to copy them to the server.

This is done in two steps. Again, we want to remove ALL of the files in the deploy folder on the server (see rationale from above)

ssh root@$SERVER "rm -rf /root/deploy/"

Next, we use scp to secure copy the files to the server

scp -r deploy root@$SERVER:/root/

Our files are now on the server!

Installing the Code

We have several steps to get through in order to install the code. They are:

- Activate the Virtual Environment

- Deleting old files

- Copying new files

- Installing Python packages

- Running Django migrations

- Collecting static files

- Reloading Gunicorn

Before we can do any of this we’ll need to ssh into our server. Once that’s done, we can proceed with the steps below.

Above we created our virtual environment in a folder called venv located in /home/yoursite/. We’ll want to activate it now (1)

source /home/yoursite/venv/bin/activate

Next, we change directory into the yoursite home directory

cd /home/yoursite/

Now, we delete the old files from the last install (2):

rm -rf /home/yoursite/yoursite

Copy our new files (3)

cp -r /root/deploy/ /home/yoursite/yoursite

Install our Python packages (4)

pip install -r /home/yoursite/yoursite/requirements.txt

Run any migrations (5)

python /home/yoursite/yoursite/manage.py migrate

Collect Static Files (6)

python /home/yoursite/yoursite/manage.py collectstatic

Finally, reload Gunicorn

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart gunicorn

When we visit our domain we should see our Django Site fn

Getting your Domain to point to Digital Ocean Your Server

I use Hover for my domain purchases and management. Why? Because they have a clean, easy to use, not-slimy interface, and because I listed to enough Tech Podcasts that I’ve drank the Kool-Aid.

When I was trying to get my Hover Domain to point to my Digital Ocean server it seemed much harder to me than it needed to be. Specifically, I couldn’t find any guide on doing it! Many of the tutorials I did find were basically like, it’s all the same. We’ll show you with GoDaddy and then you can figure it out.

Yes, I can figure it out, but it wasn’t as easy as it could have been. That’s why I’m writing this up.

Digital Ocean

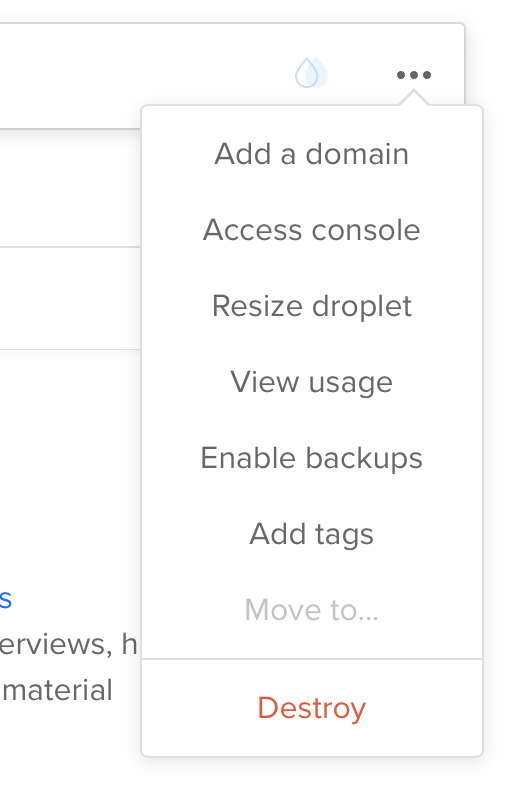

From Droplet screen click ‘Add a Domain’

<figure class="aligncenter">

</p>

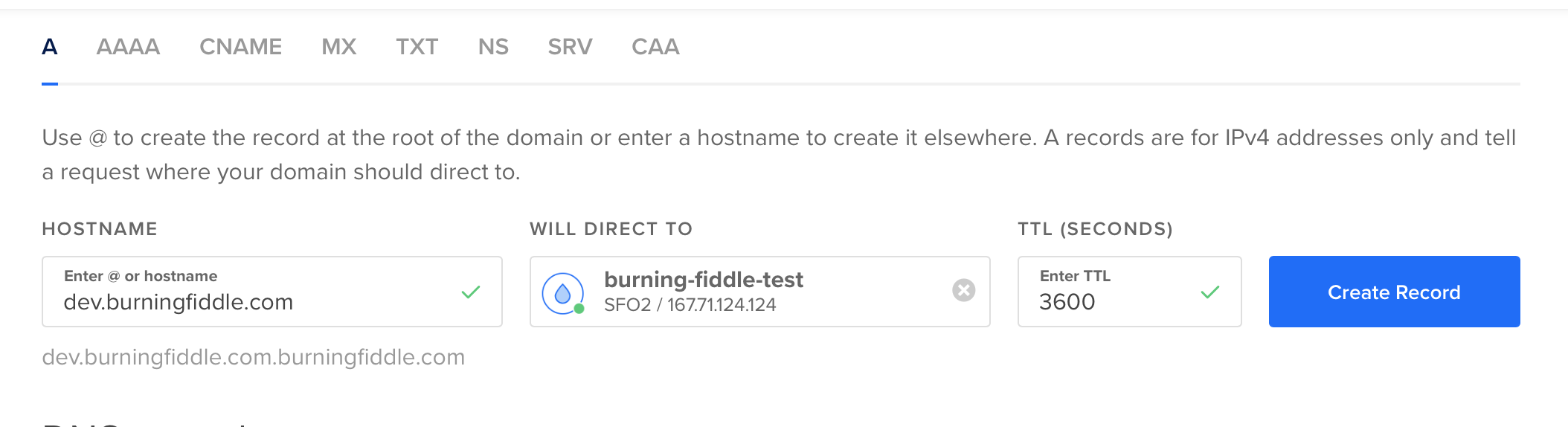

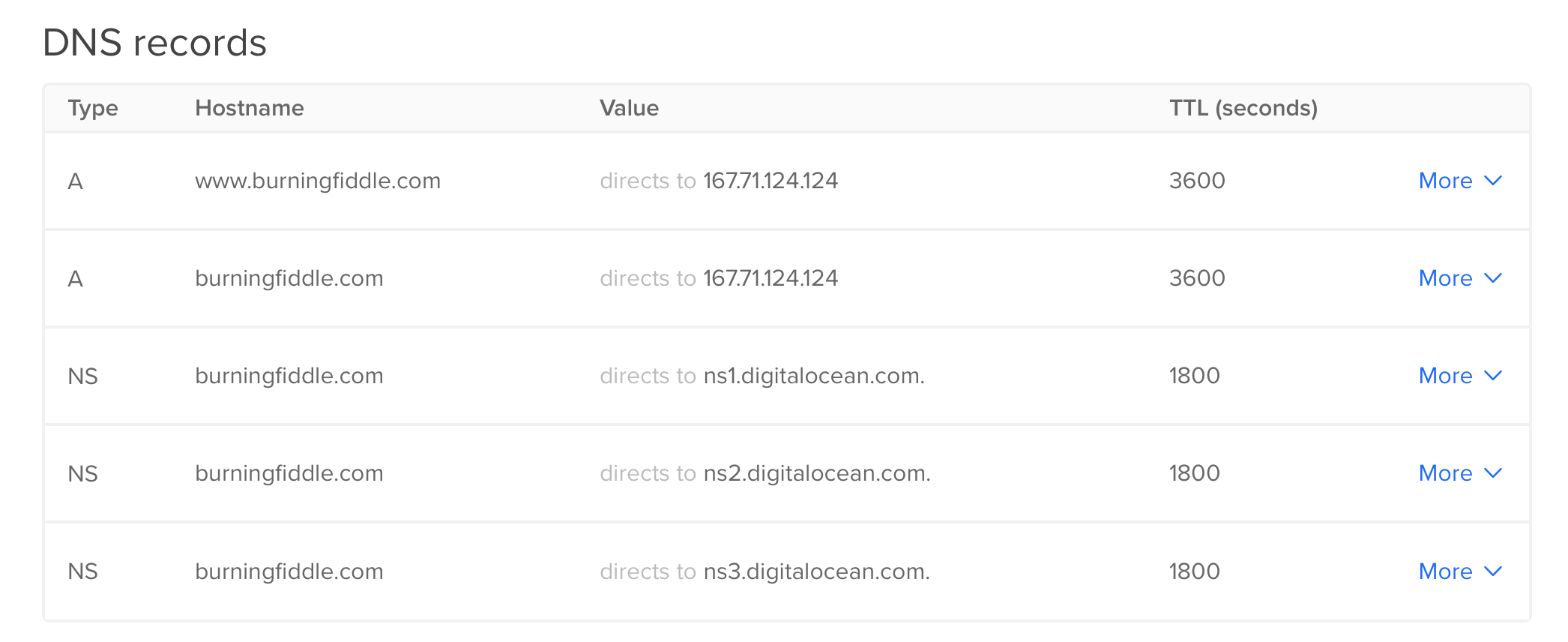

Add 2 ‘A’ records (one for www and one without the www)

Make note of the name servers

Hover

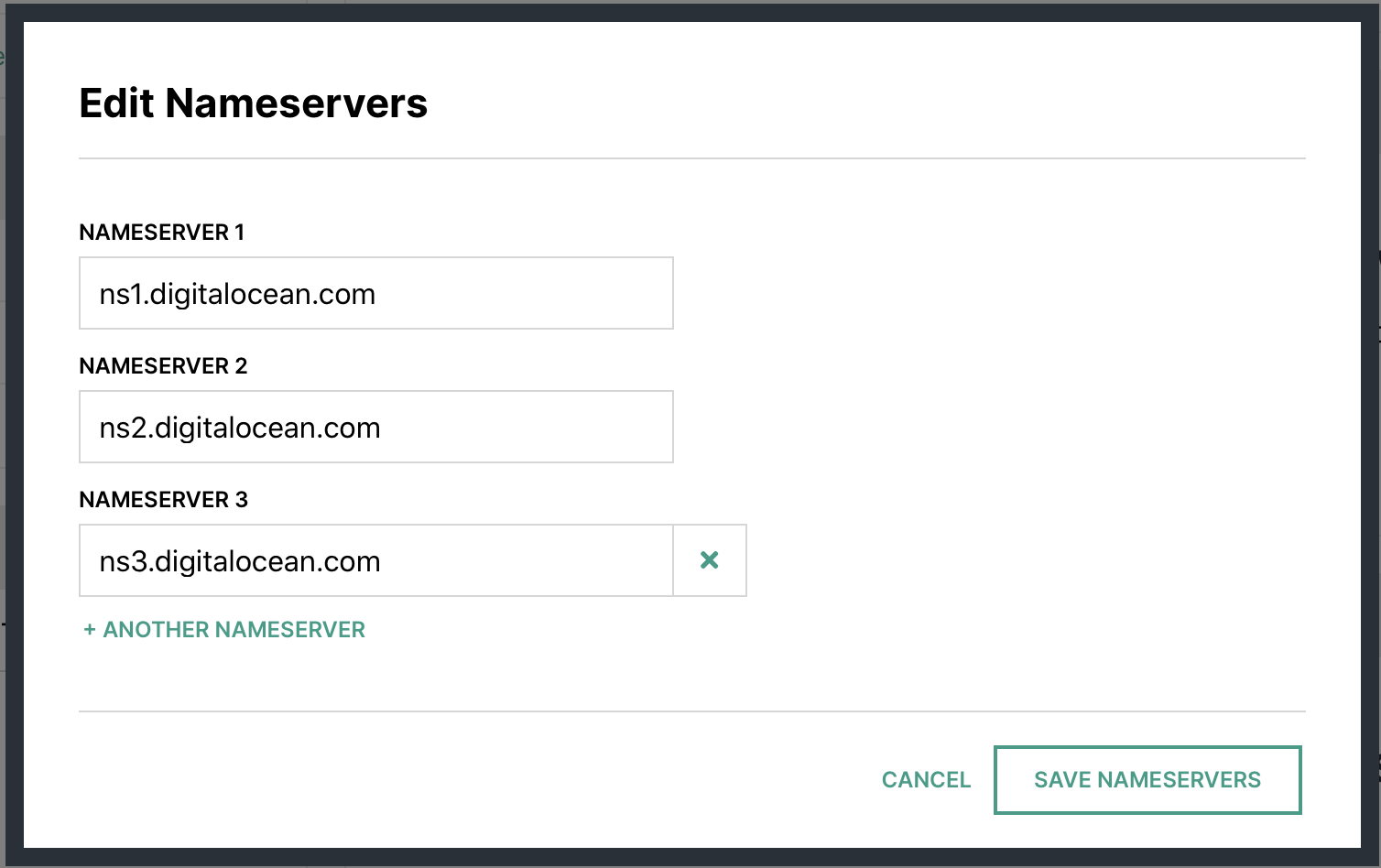

In your account at Hover.com change your Name Servers to Point to Digital Ocean ones from above.

Wait

DNS … does anyone really know how it works?1 I just know that sometimes when I make a change it’s out there almost immediately for me, and sometimes it takes hours or days.

At this point, you’re just going to potentially need to wait. Why? Because DNS that’s why. Ugh!

Setting up directory structure

While we’re waiting for the DNS to propagate, now would be a good time to set up some file structures for when we push our code to the server.

For my code deploy I’ll be using a user called burningfiddle. We have to do two things here, create the user, and add them to the www-data user group on our Linux server.

We can run these commands to take care of that:

adduser --disabled-password --gecos "" yoursite

The first line will add the user with no password and disable them to be able to log in until a password has been set. Since this user will NEVER log into the server, we’re done with the user creation piece!

Next, add the user to the proper group

adduser yoursite www-data

Now we have a user and they’ve been added to the group we need them to be added. In creating the user, we also created a directory for them in the home directory called yoursite. You should now be able to run this command without error

ls /home/yoursite/

If that returns an error indicating no such directory, then you may not have created the user properly.

Now we’re going to make a directory for our code to be run from.

mkdir /home/yoursite/yoursite

To run our Django app we’ll be using virtualenv. We can create our virtualenv directory by running this command

python3 -m venv /home/yoursite/venv

Configuring Gunicorn

There are two files needed for Gunicorn to run:

- gunicorn.socket

- gunicorn.service

For our setup, this is what they look like:

# gunicorn.socket

[Unit]

Description=gunicorn socket

[Socket]

ListenStream=/run/gunicorn.sock

[Install]

WantedBy=sockets.target

# gunicorn.service

[Unit]

Description=gunicorn daemon

Requires=gunicorn.socket

After=network.target

[Service]

User=yoursite

EnvironmentFile=/etc/environment

Group=www-data

WorkingDirectory=/home/yoursite/yoursite

ExecStart=/home/yoursite/venv/bin/gunicorn

--access-logfile -

--workers 3

--bind unix:/run/gunicorn.sock

yoursite.wsgi:application

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

For more on the details of the sections in both gunicorn.service and gunicorn.socket see this article.

Environment Variables

The only environment variables we have to worry about here (since we’re using SQLite) are the DJANGO_SECRET_KEY and DJANGO_DEBUG

We’ll want to edit /etc/environment with our favorite editor (I’m partial to vim but use whatever you like

vim /etc/environment

In this file you’ll add your DJANGO_SECRET_KEY and DJANGO_DEBUG. The file will look something like this once you’re done:

PATH="/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games"

DJANGO_SECRET_KEY=my_super_secret_key_goes_here

DJANGO_DEBUG=False

Setting up Nginx

Now we need to create our .conf file for Nginx. The file needs to be placed in /etc/nginx/sites-available/$sitename where $sitename is the name of your site. fn

The final file will look (something) like this fn

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.yoursite.com yoursite.com;

location = /favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /home/yoursite/yoursite/;

}

location / {

include proxy_params;

proxy_pass http://unix:/run/gunicorn.sock;

}

}

The .conf file above tells Nginx to listen for requests to either www.buringfiddle.com or buringfiddle.com and then route them to the location /home/yoursite/yoursite/ which is where our files are located for our Django project.

With that in place all that’s left to do is to make it enabled by running replacing $sitename with your file

ln -s /etc/nginx/sites-available/$sitename /etc/nginx/sites-enabled

You’ll want to run

nginx -t

to make sure there aren’t any errors. If no errors occur you’ll need to restart Nginx

systemctl restart nginx

The last thing to do is to allow full access to Nginx. You do this by running

ufw allow 'Nginx Full'

- Probably just [Julia Evans](https://jvns.ca/blog/how-updating-dns-works/ ↩︎

Setting up the Server (on Digital Ocean)

The initial setup

Digital Ocean has a pretty nice API which makes it easy to automate the creation of their servers (which they call Droplets. This is nice when you’re trying to work towards automation of the entire process (like I was).

I won’t jump into the automation piece just yet, but once you have your DO account setup (sign up here if you don’t have one), it’s a simple interface to Setup Your Droplet.

I chose the Ubuntu 18.04 LTS image with a \$5 server (1GB Ram, 1CPU, 25GB SSD Space, 1000GB Transfer) hosted in their San Francisco data center (SFO21).

We’ve got a server … now what?

We’re going to want to update, upgrade, and install all of the (non-Python) packages for the server. For my case, that meant running the following:

apt-get update

apt-get upgrade

apt-get install python3 python3-pip python3-venv tree postgresql postgresql-contrib nginx

That’s it! We’ve now got a server that is ready to be setup for our Django Project.

In the next post, I’ll walk through how to get your Domain Name to point to the Digital Ocean Server.

- SFO2 is disabled for new customers and you will now need to use SFO3 unless you already have resources on SFO2, but if you’re following along you probably don’t. What’s the difference between the two? Nothing 😁 ↩︎

Writing tests for Django Admin Custom Functionality

I’ve been working on a Django app side project for a while and came across the need to write a custom filter for the Django Admin section.

This was a first for me, and it was pretty straight forward to accomplish the task. I wanted to add a filter on the drop down list so that only certain records would appear.

To do this, I sub-classed the Django Admin SimpleListFilter with the following code:

class EmployeeListFilter(admin.SimpleListFilter):

title = "Employee"

parameter_name = "employee"

def lookups(self, request, model_admin):

employees = []

qs = Employee.objects.filter(status__status="Active").order_by("first_name", "last_name")

for employee in qs:

employees.append((employee.pk, f"{employee.first_name} {employee.last_name}"))

return employees

def queryset(self, request, queryset):

if self.value():

qs = queryset.filter(employee__id=self.value())

else:

qs = queryset

return qs

And implemented it like this:

@admin.register(EmployeeO3Note)

class EmployeeO3NoteAdmin(admin.ModelAdmin):

list_filter = (EmployeeListFilter, "o3_date")

This was, as I said, relatively straight forward to do, but what was less clear to me was how to write tests for this functionality. My project has 100% test coverage, and therefore testing isn’t something I’m unfamiliar with, but in this context, I wasn’t sure where to start.

There are two parts that need to be tested:

lookupsqueryset

Additionally, the querysethas two states that need to be tested

- With

self.value() - Without

self.value()

This gives a total of 3 tests to write

The thing that helps me out the most when trying to determine how to write tests is to use the Django Shell in PyCharm. To do this I:

- Import necessary parts of Django App

- Instantiate the

EmployeeListFilter - See what errors I get

- Google how to fix the errors

- Repeat

This is what the test ended up looking like:

import pytest

from employees.models import EmployeeO3Note

from employees.tests.factories import EmployeeFactory, EmployeeO3NoteFactory, EmployeeStatusFactory

from employees.admin import EmployeeListFilter

ACTIVE_EMPLOYEES = 3

TERMED_EMPLOYEES = 1

@pytest.fixture

def active_employees():

return EmployeeFactory.create_batch(ACTIVE_EMPLOYEES)

@pytest.fixture

def termed_employees():

termed_employees = TERMED_EMPLOYEES

termed = EmployeeStatusFactory(status="Termed")

return EmployeeFactory.create_batch(termed_employees, status=termed)

@pytest.fixture

def o3_notes_for_all_employees(active_employees, termed_employees):

all_employees = active_employees + termed_employees

o3_notes = []

for i in range(len(all_employees)):

o3_notes.append(EmployeeO3NoteFactory.create_batch(1, employee=all_employees[i]))

return o3_notes

@pytest.mark.django_db

def test_admin_filter_active_employee_o3_notes(active_employees):

employee_list_filter = EmployeeListFilter(request=None, params={}, model=None, model_admin=None)

assert len(employee_list_filter.lookup_choices) == ACTIVE_EMPLOYEES

@pytest.mark.django_db

def test_admin_query_set_unfiltered_results_o3_notes(o3_notes_for_all_employees):

total_employees = ACTIVE_EMPLOYEES + TERMED_EMPLOYEES

employee_list_filter = EmployeeListFilter(request=None, params={}, model=None, model_admin=None)

assert len(employee_list_filter.queryset(request=None, queryset=EmployeeO3Note.objects.all())) == total_employees

@pytest.mark.django_db

def test_admin_query_set_filtered_results_o3_notes(active_employees, o3_notes_for_all_employees):

employee_to_test = active_employees[0]

employee_list_filter = EmployeeListFilter(

request=None, params={"employee": employee_to_test.pk}, model=None, model_admin=None

)

queryset_to_test = employee_list_filter.queryset(request=None, queryset=EmployeeO3Note.objects.all())

assert len(queryset_to_test.filter(employee__id=employee_to_test.pk)) == 1

Deploying a Django Site to Digital Ocean - A Series

Previous Efforts

When I first heard of Django I thought it looks like a really interesting, and Pythonic way, to get a website up and running. I spent a whole weekend putting together a site locally and then, using Digital Ocean, decided to push my idea up onto a live site.

One problem that I ran into, which EVERY new Django Developer will run into was static files. I couldn’t get static files to work. No matter what I did, they were just … missing. I proceeded to spend the next few weekends trying to figure out why, but alas, I was not very good (or patient) with reading documentation and gave up.

Fast forward a few years, and while taking the 100 Days of Code on the Web Python course from Talk Python to Me I was able to follow along on a part of the course that pushed up a Django App to Heroku.

I wrote about that effort here. Needless to say, I was pretty pumped. But, I was wondering, is there a way I can actually get a Django site to work on a non-Heroku (PaaS) type infrastructure.

Inspiration

While going through my Twitter timeline I cam across a retweet from TestDrive.io of Matt Segal. He has an amazing walk through of deploying a Django site on the hard level (i.e. using Windows). It’s a mix of Blog posts and YouTube Videos and I highly recommend it. There is some NSFW language, BUT if you can get past that (and I can) it’s a great resource.

This series is meant to be a written record of what I did to implement these recommendations and suggestions, and then to push myself a bit further to expand the complexity of the app.

Articles

A list of the Articles will go here. For now, here’s a rough outline of the planned posts:

- Setting up the Server (on Digital Ocean)

- Getting your Domain to point to Digital Ocean Your Server

- Preparing the code for deployment to Digital Ocean

- Automating the deployment

- Enhancements

The ‘Enhancements’ will be multiple follow up posts (hopefully) as I catalog improvements make to the site. My currently planned enhancements are:

- Creating the App

- Migrating from SQLite to Postgres

- Integrating Git

- Having Multiple Sites on a single Server

- Adding Caching

- Integrating S3 on AWS to store Static Files and Media Files

- Migrate to Docker / Kubernetes

Django form filters

I’ve been working on a Django Project for a while and one of the apps I have tracks candidates. These candidates have dates of a specific type.

The models look like this:

Candidate

class Candidate(models.Model):

first_name = models.CharField(max_length=128)

last_name = models.CharField(max_length=128)

resume = models.FileField(storage=PrivateMediaStorage(), blank=True, null=True)

cover_leter = models.FileField(storage=PrivateMediaStorage(), blank=True, null=True)

email_address = models.EmailField(blank=True, null=True)

linkedin = models.URLField(blank=True, null=True)

github = models.URLField(blank=True, null=True)

rejected = models.BooleanField()

position = models.ForeignKey(

"positions.Position",

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

)

hired = models.BooleanField(default=False)

CandidateDate

class CandidateDate(models.Model):

candidate = models.ForeignKey(

"Candidate",

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

)

date_type = models.ForeignKey(

"CandidateDateType",

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

)

candidate_date = models.DateField(blank=True, null=True)

candidate_date_note = models.TextField(blank=True, null=True)

meeting_link = models.URLField(blank=True, null=True)

class Meta:

ordering = ["candidate", "-candidate_date"]

unique_together = (

"candidate",

"date_type",

)

CandidateDateType

class CandidateDateType(models.Model):

date_type = models.CharField(max_length=24)

description = models.CharField(max_length=255, null=True, blank=True)

You’ll see from the CandidateDate model that the fields candidate and date_type are unique. One problem that I’ve been running into is how to help make that an easier thing to see in the form where the dates are entered.

The Django built in validation will display an error message if a user were to try and select a candidate and date_type that already existed, but it felt like this could be done better.

I did a fair amount of Googling and had a couple of different bright ideas, but ultimately it came down to a pretty simple implementation of the exclude keyword in the ORM

The initial Form looked like this:

class CandidateDateForm(ModelForm):

class Meta:

model = CandidateDate

fields = [

"candidate",

"date_type",

"candidate_date",

"meeting_link",

"candidate_date_note",

]

widgets = {

"candidate": HiddenInput,

}

I updated it to include a __init__ method which overrode the options in the drop down.

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super(CandidateDateForm, self).__init__(*args, **kwargs)

try:

candidate = kwargs["initial"]["candidate"]

candidate_date_set = CandidateDate.objects.filter(candidate=candidate).values_list("date_type", flat=True)

qs = CandidateDateType.objects.exclude(id__in=candidate_date_set)

self.fields["date_type"].queryset = qs

except KeyError:

pass

Now, with this method the drop down will only show items which can be selected, not all CandidateDateType options.

Seems like a better user experience AND I got to learn a bit about the Django ORM

Using different .env files

In a Django project I’m working on I use a library called Django-environ which

allows you to utilize 12factor inspired environment variables to configure your Django application.

It’s a pretty sweet library as well. You create a .env file to store your variable that you don’t want in a public repo for your settings.py.

The big issue I have is that my .env file for my local development isn’t what I want on my production server (obviously ... never set DEBIG=True in production!)

I had tried to use a different .env file using an assortment of methods, but to no avail. And the documentation wasn’t much of a help for using Multiple env file

It is possible to have multiple env files and select one using environment variables.

Now

ENV_PATH=other-env ./manage.py runserverusesother-envwhile./manage.py runserveruses.env.

But there’s no example about how to actually set that up 🤦🏻♂️1.

In fact, this bit in the documentation reminded me of thisvideo on YouTube.

Instead of trying to figure out the use of multiple .env files I instead used a just recipe in my justfile to get the job done.

# checks the deployment for prod settings; will return error if the check doesn't pass

check:

cp core/.env core/.env_staging

cp core/.env_prod core/.env

-python manage.py check --deploy

cp core/.env_staging core/.env

OK. What does this recipe do?

First, we copy the development .env file to a .env_staging file to keep the original development settings ‘somewhere’

cp core/.env core/.env_staging

Next, we copy the .env_prod to the .env so that we can use it when we run -python manage.py check --deploy.

cp core/.env_prod core/.env

-python manage.py check --deploy

Why do we use the -? That allows the justfile to keep going if it runs into an error. Since we’re updating our main .env file I want to make sure it gets restored to its original state … just in case!

Finally, we copy the original contents of the .env file from the .env_staging back to the .env to restore it to its development settings.

Now, I can simply run

just check

And I’ll know if I have passed the 12 factor checking for my Django project or somehow introduced something that makes the check not pass.

I’d like to figure out how to set up multiple .env files, create an example and contribute to the docs ... but honestly I have no freaking clue how to do it. If I am able to figure it out, you can bet I’m going to write up a PR for the docs!

- I’d like to figure out how to set up multiple

.envfiles, create an example and contribute to the docs ... but honestly I have no freaking clue how to do it. If I am able to figure it out, you can bet I’m going to write up a PR for the docs! ↩︎

Logging in a Django App

Per the Django Documentation you can set up

A list of all the people who get code error notifications. When DEBUG=False and AdminEmailHandler is configured in LOGGING (done by default), Django emails these people the details of exceptions raised in the request/response cycle.

In order to set this up you need to include in your settings.py file something like:

ADMINS = [

('John', 'john@example.com'),

('Mary', 'mary@example.com')

]

The difficulties I always ran into were:

- How to set up the AdminEmailHandler

- How to set up a way to actually email from the Django Server

Again, per the Django Documentation:

Django provides one log handler in addition to those provided by the Python logging module

Reading through the documentation didn’t really help me all that much. The docs show the following example:

'handlers': {

'mail_admins': {

'level': 'ERROR',

'class': 'django.utils.log.AdminEmailHandler',

'include_html': True,

}

},

That’s great, but there’s not a direct link (that I could find) to the example of how to configure the logging in that section. It is instead at the VERY bottom of the documentation page in the Contents section in the Configured logging > Examples section ... and you really need to know that you have to look for it!

The important thing to do is to include the above in the appropriate LOGGING setting, like this:

LOGGING = {

'version': 1,

'disable_existing_loggers': False,

'handlers': {

'mail_admins': {

'level': 'ERROR',

'class': 'django.utils.log.AdminEmailHandler',

'include_html': True,

}

},

},

}

Sending an email with Logging information

We’ve got the logging and it will be sent via email, but there’s no way for the email to get sent out yet!

In order to accomplish this I use SendGrid. No real reason other than that’s what I’ve used in the past.

There are great tutorials online for how to get SendGrid integrated with Django, so I won’t rehash that here. I’ll just drop my the settings I used in my settings.py

SENDGRID_API_KEY = env("SENDGRID_API_KEY")

EMAIL_HOST = "smtp.sendgrid.net"

EMAIL_HOST_USER = "apikey"

EMAIL_HOST_PASSWORD = SENDGRID_API_KEY

EMAIL_PORT = 587

EMAIL_USE_TLS = True

One final thing I needed to do was to update the email address that was being used to send the email. By default it uses root@localhost which isn’t ideal.

You can override this by setting

SERVER_EMAIL = myemail@mydomain.tld

With those three settings, everything should just work.

Page 11 / 24