Setting up the Server to host my Pelican Site

Creating the user on the server

Each site on my server has it's own user. This is a security consideration, more than anything else. For this site, I used the steps from some of my scripts for setting up a Django site. In particular, I ran the following code from the shell on the server:

adduser --disabled-password --gecos "" ryancheley

adduser ryancheley www-data

The first command above creates the user with no password so that they can't actually log in. It also creates the home directory /home/ryancheley. This is where the site will be server from.

The second commands adds the user to the www-data group. I don't think that's strictly necessary here, but in order to keep this user consistent with the other web site users, I ran it to add it to the group.

Creating the nginx config file

For the most part I cribbed the nginx config files from this blog post.

There were some changes that were required though. As I indicated in part 1, I had several requirements I was trying to fulfill, most notably not breaking historic links.

Here is the config file for my UAT site (the only difference between this and the prod site is the server name on line 3):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 | |

The most interesting part of the code above is the location block from lines 6 - 11.

location / {

# Serve a .gz version if it exists

gzip_static on;

error_page 404 /404.html;

rewrite ^/index.php/(.*) /$1 permanent;

}

Custom 404 Page

error_page 404 /404.html;

This line is what allows me to have a custom 404 error page. If a page is not found nginx will serve up the html page 404.html which is generated by a markdown file in my pages directory and looks like this:

Title: Not Found

Status: hidden

Save_as: 404.html

The requested item could not be located.

I got this implementation idea from the Pelican docs.

Rewrite rule for index.php in the URL

rewrite ^/index.php/(.*) /$1 permanent;

The rewrite line fixes the index.php challenge I mentioned in the previous post

It took me a really long time to figure this out because the initial config file had a location block that looked like this:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

I didn't recognize the location = / { on line 1 as being different than the location block above starting at line 6. So I added

rewrite ^/index.php/(.*) /$1 permanent;

to that block and it NEVER worked because it never could.

The = in the location block indicates a literal exact match, which the regular expression couldn't do because it's trying to be dynamic, but the = indicates static 🤦🏻♂️

OK, we've got a user, and we've got a configuration file, now all we need is a way to get the files to the server.

I'll go over that in the next post.

Migrating to Pelican from Wordpress

A little back story

In October of 2017 I wrote about how I migrated from SquareSpace to Wordpress. After almost 4 years I’ve decided to migrate again, this time to Pelican. I did a bit of work with Pelican during my 100 Days of Web Code back in 2019.

A good question to ask is, “why migrate to a new platform” The answer, is that while writing my post Debugging Setting up a Django Project I had to go back and make a change. It was the first time I’d ever had to use the WordPress Admin to write anything ... and it was awful.

My writing and posting workflow involves Ulysses where I write everything in MarkDown. Having to use the WYSIWIG interface and the ‘blocks’ in WordPress just broke my brain. That meant what should have been a slight tweak ended up taking me like 45 minutes.

I decided to give Pelican a shot in a local environment to see how it worked. And it turned out to work very well for my brain and my writing style.

Setting it up

I set up a local instance of Pelican using the Quick Start guide in the docs.

Pelican has a CLI utility that converts the xml into Markdown files. This allowed me to export my Wordpress blog content to it’s XML output and save it in the Pelican directory I created.

I then ran the command:

pelican-import --wp-attach -o ./content ./wordpress.xml

This created about 140 .md files

Next, I ran a few Pelican commands to generate the output:

pelican content

and then the local web server:

pelican --listen

I reviewed the page and realized there was a bit of clean up that needed to be done. I had categories of Blog posts that only had 1 article, and were really just a different category that needed to be tagged appropriately. So, I made some updates to the categorization and tagging of the posts.

I also had some broken links I wanted to clean up so I took the opportunity to check the links on all of the pages and make fixes where needed. I used the library LinkChecker which made the process super easy. It is a CLI that generates HTML that you can then review. Pretty neat.

Deploying to a test server

The first thing to do was to update my DNS for a new subdomain to point to my UAT server. I use Hover and so it was pretty easy to add the new entry.

I set uat.ryancheley.com to the IP Address 178.128.188.134

Next, in order to have UAT serve requests for my new site I need to have a configuration file for Nginx. This post gave me what I needed as a starting point for the config file. Specifically it gave me the location blocks I needed:

location = / {

# Instead of handling the index, just

# rewrite / to /index.html

rewrite ^ /index.html;

}

location / {

# Serve a .gz version if it exists

gzip_static on;

# Try to serve the clean url version first

try_files $uri.htm $uri.html $uri =404;

}

With that in hand I deployed my pelican site to the server

The first thing I noticed was that the URLs still had index.php in them. This is a hold over from how my WordPress URL schemes were set up initially that I never got around to fixing but it’s always something that’s bothered me.

My blog may not be something that is linked to a ton (or at all?), but I didn’t want to break any links if I didn’t have to, so I decided to investigate Nginx rewrite rules.

I spent a bit of time trying to get my url to from this:

https://www.ryancheley.com/index.php/2017/10/01/migrating-from-square-space-to-word-press/

to this:

https://www.ryancheley.com/migrating-from-square-space-to-word-press/

using rewrite rules.

I gave up after several hours of trying different things. This did lead me to some awesome settings for Pelican that would allow me to retain the legacy Wordpress linking structure, so I updated the settings file to include this line:

ARTICLE_URL = 'index.php/{date:%Y}/{date:%m}/{date:%d}/{slug}/'

ARTICLE_SAVE_AS = 'index.php/{date:%Y}/{date:%m}/{date:%d}/{slug}/index.html'

OK. I still have the index.php issue, but at least my links won’t break.

404 Not Found

I starting testing the links on the site just kind of clicking here and there and discovered a couple of things:

- The menu links didn’t always work

- The 404 page wasn’t styled like I wanted it to me styled

The pelican documentation has an example for creating your own 404 pages which also includes what to update the Nginx config file location block.

And this is what lead me to discover what I had been doing wrong for the rewrites earlier!

There are two location blocks in the example code I took, but I didn’t see how they were different.

The first location block is:

location = / {

# Instead of handling the index, just

# rewrite / to /index.html

rewrite ^ /index.html;

}

Per the Nginx documentation the =

If an equal sign is used, this block will be considered a match if the request URI exactly matches the location given.

BUT since I was trying to use a regular expression, it wasn’t matching exactly and so it wasn’t ‘working’

The second location block was not an exact match (notice there is no = in the first line:

location / {

# Serve a .gz version if it exists

gzip_static on;

# Try to serve the clean url version first

try_files $uri.htm $uri.html $uri =404;

}

When I added the error page setting for Pelican I also added the URL rewrite rules to remove the index.php and suddenly my dream of having the redirect rules worked!

Additionally, I didn’t need the first location block at all. The final location block looks like this:

location / {

# Serve a .gz version if it exists

gzip_static on;

# Try to serve the clean url version first

# try_files $uri.htm $uri.html $uri =404;

error_page 404 /404.html;

rewrite ^/index.php/(.*) /$1 permanent;

}

I was also able to update my Pelican settings to this:

ARTICLE_URL = '{date:%Y}/{date:%m}/{date:%d}/{slug}/'

ARTICLE_SAVE_AS = '{date:%Y}/{date:%m}/{date:%d}/{slug}/index.html'

Victory!

What I hope to gain from moving

In my post outlining the move from SquareSpace to Wordpress I said,

As I wrote earlier my main reason for leaving Square Space was the difficulty I had getting content in. So, now that I’m on a WordPress site, what am I hoping to gain from it?

- Easier to post my writing

- See Item 1

Writing is already really hard for me. I struggle with it and making it difficult to get my stuff out into the world makes it that much harder. My hope is that not only will I write more, but that my writing will get better because I’m writing more.

So, what am I hoping to gain from this move:

- Just as easy to write my posts

- Easier to edit my posts

Writing is still hard for me (nearly 4 years later) and while moving to a new shiny tool won’t make the thinking about writing any easier, maybe it will make the process of writing a little more fun and that may lead to more words!

Addendum

There are already a lot of words here and I have more to say on this. I plan on writing a couple of more posts about the migration:

- Setting up the server to host Pelican

- The writing workflow used

Debugging Setting up a Django Project

Normally when I start a new Django project I’ll use the PyCharm setup wizard, but recently I wanted to try out VS Code for a Django project and was super stumped when I would get a message like this:

ERROR:root:code for hash md5 was not found.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 147, in <module>

globals()[__func_name] = __get_hash(__func_name)

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 97, in __get_builtin_constructor

raise ValueError('unsupported hash type ' + name)

ValueError: unsupported hash type md5

ERROR:root:code for hash sha1 was not found.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 147, in <module>

globals()[__func_name] = __get_hash(__func_name)

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 97, in __get_builtin_constructor

raise ValueError('unsupported hash type ' + name)

ValueError: unsupported hash type sha1

ERROR:root:code for hash sha224 was not found.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 147, in <module>

globals()[__func_name] = __get_hash(__func_name)

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 97, in __get_builtin_constructor

raise ValueError('unsupported hash type ' + name)

ValueError: unsupported hash type sha224

ERROR:root:code for hash sha256 was not found.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 147, in <module>

globals()[__func_name] = __get_hash(__func_name)

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 97, in __get_builtin_constructor

raise ValueError('unsupported hash type ' + name)

ValueError: unsupported hash type sha256

ERROR:root:code for hash sha384 was not found.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 147, in <module>

globals()[__func_name] = __get_hash(__func_name)

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 97, in __get_builtin_constructor

raise ValueError('unsupported hash type ' + name)

ValueError: unsupported hash type sha384

ERROR:root:code for hash sha512 was not found.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 147, in <module>

globals()[__func_name] = __get_hash(__func_name)

File "/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/2.7/lib/python2.7/hashlib.py", line 97, in __get_builtin_constructor

raise ValueError('unsupported hash type ' + name)

ValueError: unsupported hash type sha512

Here are the steps I was using to get started

From a directory I wanted to create the project I would set up my virtual environment

python3 -m venv venv

And then activate it

source venv/bin/activate

Next, I would install Django

pip install django

Next, using the startproject command per the docs I would

django-admin startproject my_great_project .

And get the error message above 🤦🏻♂️

The strangest part about the error message is that it references Python2.7 everywhere … which is odd because I’m in a Python3 virtual environment.

I did a pip list and got:

Package Version

---------- -------

asgiref 3.3.4

Django 3.2.4

pip 21.1.2

pytz 2021.1

setuptools 49.2.1

sqlparse 0.4.1

OK … so everything is in my virtual environment. Let’s drop into the REPL and see what’s going on

Well, that looks to be OK.

Next, I checked the contents of my directory using tree -L 2

├── manage.py

├── my_great_project

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

└── venv

├── bin

├── include

├── lib

└── pyvenv.cfg

Yep … that looks good too.

OK, let’s go look at the installed packages for Python 2.7 then. On macOS they’re installed at

/usr/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages

Looking in there and I see that Django is installed.

OK, let’s use pip to uninstall Django from Python2.7, except that pip gives essentially the same result as running the django-admin command.

OK, let’s just remove it manually. After a bit of googling I found this Stackoverflow answer on how to remove the offending package (which is what I assumed would be the answer, but better to check, right?)

After removing the Django install from Python 2.7 and running django-admin --version I get

So I googled that error message and found another answers on Stackoverflow which lead me to look at the manage.py file. When I cat the file I get:

# manage.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

import os

import sys

...

That first line SHOULD be finding the Python executable in my virtual environment, but it’s not.

Next I googled the error message django-admin code for hash sha384 was not found

Which lead to this Stackoverflow answer. I checked to see if Python2 was installed with brew using

brew leaves | grep python

which returned python@2

Based on the answer above, the solution was to uninstall the Python2 that was installed by brew. Now, although Python2 has retired, I was leery of uninstalling it on my system without first verifying that I could remove the brew version without impacting the system version which is needed by macOS.

Using brew info python@2 I determined where brew installed Python2 and compared it to where Python2 is installed by macOS and they are indeed different

Output of brew info python@2

...

/usr/local/Cellar/python@2/2.7.15_1 (7,515 files, 122.4MB) *

Built from source on 2018-08-05 at 15:18:23

...

Output of which python

/usr/bin/python

OK, now we can remove the version of Python2 installed by brew

brew uninstall python@2

Now with all of that cleaned up, lets try again. From a clean project directory:

python3 -m venv venv

source venv/bin/activate

pip install django

django-admin --version

The last command returned

zsh: /usr/local/bin/django-admin: bad interpreter: /usr/local/opt/python@2/bin/python2.7: no such file or directory

3.2.4

OK, I can get the version number and it mostly works, but can I create a new project?

django-admin startproject my_great_project .

Which returns

zsh: /usr/local/bin/django-admin: bad interpreter: /usr/local/opt/python@2/bin/python2.7: no such file or directory

BUT, the project was installed

├── db.sqlite3

├── manage.py

├── my_great_project

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── __pycache__

│ ├── asgi.py

│ ├── settings.py

│ ├── urls.py

│ └── wsgi.py

└── venv

├── bin

├── include

├── lib

└── pyvenv.cfg

And I was able to run it

python manage.py runserver

Success! I’ve still got that last bug to deal with, but that’s a story for a different day!

Short Note

My initial fix, and my initial draft for this article, was to use the old adage, turn it off and turn it back on. In this case, the implementation would be the deactivate and then re activate the virtual environment and that’s what I’d been doing.

As I was writing up this article I was hugely influenced by the work of Julie Evans and kept asking, “but why?”. She’s been writing a lot of awesome, amazing things, and has several zines for purchase that I would highly recommend.

She’s also generated a few debugging ‘games’ that are a lot of fun.

Anyway, thanks Julie for pushing me to figure out the why for this issue.

Post Script

I figured out the error message above and figured, well, I might as well update the post! I thought it had to do with zsh, but no, it was just more of the same.

The issue was that Django had been installed in the base Python2 (which I knew). All I had to do was to uninstall it with pip.

pip uninstall django

The trick was that pip wasn't working out for me ... it was generating errors. So I had to run the command

python -m pip uninstall django

I had to run this AFTER I put the Django folder back into /usr/local/lib/python2.7/site-packages (if you'll recall from above, I removed it from the folder)

After that clean up was done, everything worked out as expected! I just had to keep digging!

My First Python Package

A few months ago I was inspired by Simon Willison and his project Datasette and it’s related ecosystem to write a Python Package for it.

I use toggl to track my time at work and I thought this would be a great opportunity use that data with Datasette and see if I couldn’t answer some interesting questions, or at the very least, do some neat data discovery.

The purpose of this package is to:

Create a SQLite database containing data from your toggl account

I followed the tutorial for committing a package to PyPi and did the first few pushes manually. Then, using a GitHub action from one of Simon’s Datasette projects, I was able to automate it when I make a release on GitHub!

Since the initial commit on March 7 (my birthday BTW) I’ve had 10 releases, with the most recent one coming yesterday which removed an issue with one of the tables reporting back an API key which, if published on the internet could be a bad thing ... so hooray for security enhancements!

Anyway, it was a fun project, and got me more interested in authoring Python packages. I’m hoping to do a few more related to Datasette (although I’m not sure what to write honestly!).

Be sure to check out the package on PyPi.org and the source code on GitHub.

How does my Django site connect to the internet anyway?

I created a Django site to troll my cousin Barry who is a big San Diego Padres fan. Their Shortstop is a guy called Fernando Tatis Jr. and he’s really good. Like really good. He’s also young, and arrogant, and is everything an old dude like me doesn’t like about the ‘new generation’ of ball players that are changing the way the game is played.

In all honesty though, it’s fun to watch him play (anyone but the Dodgers).

The thing about him though, is that while he’s really good at the plate, he’s less good at playing defense. He currently leads the league in errors. Not just for all shortstops, but for ALL players!

Anyway, back to the point. I made this Django site call Does Tatis Jr Have an Error Today?It is a simple site that only does one thing ... tells you if Tatis Jr has made an error today. If he hasn’t, then it says No, and if he has, then it says Yes.

It’s a dumb site that doesn’t do anything else. At all.

But, what it did do was lead me down a path to answer the question, “How does my site connect to the internet anyway?”

Seems like a simple enough question to answer, and it is, but it wasn’t really what I thought when I started.

How it works

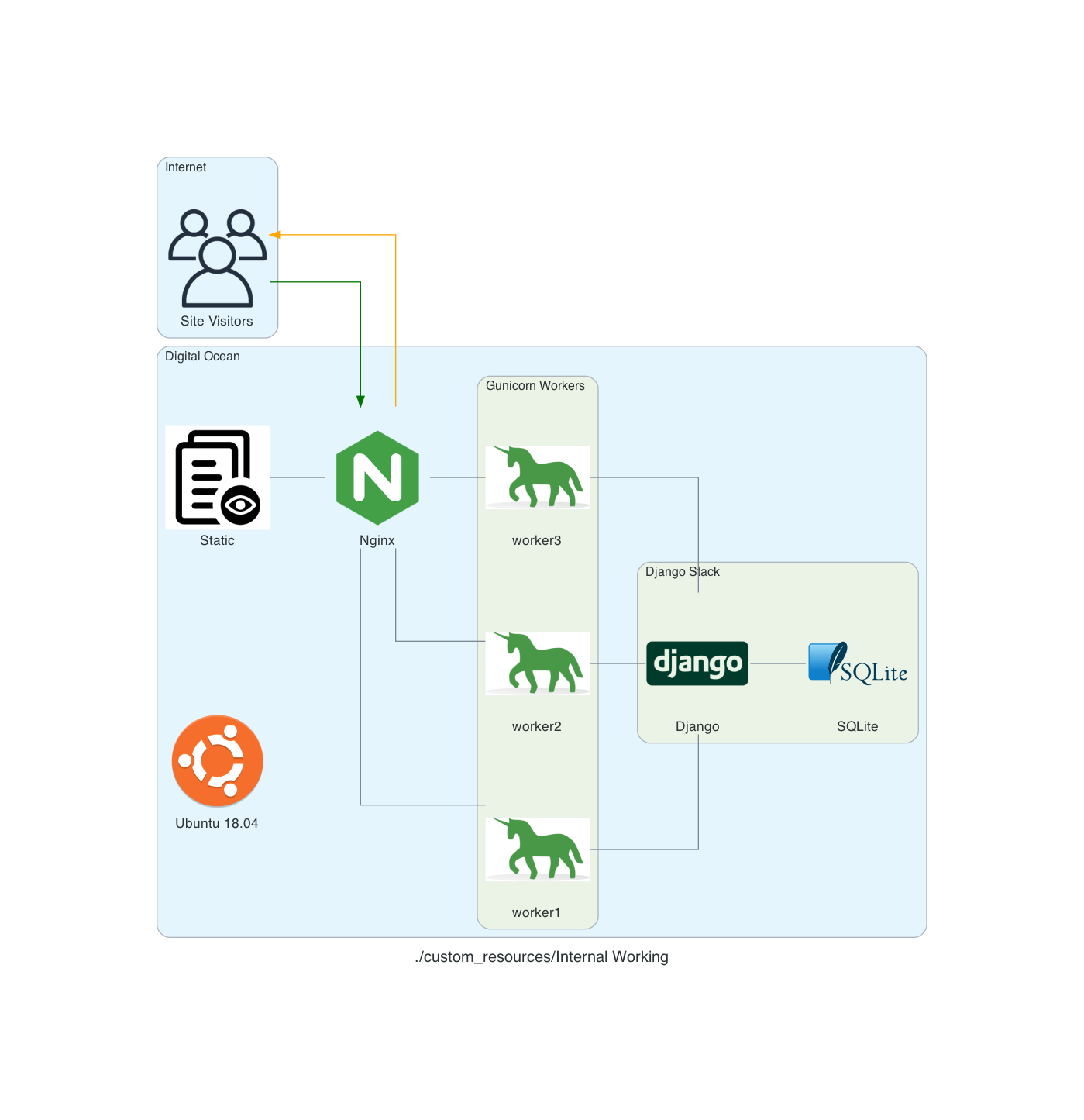

I use a MacBook Pro to work on the code. I then deploy it to a Digital Ocean server using GitHub Actions. But they say, a picture is worth a thousand words, so here's a chart of the workflow:

This shows the development cycle, but that doesn’t answer the question, how does the site connect to the internet!

How is it that when I go to the site, I see anything? I thought I understood it, and when I tried to actually draw it out, turns out I didn't!

After a bit of Googling, I found this and it helped me to create this:

My site runs on an Ubuntu 18.04 server using Nginx as proxy server. Nginx determines if the request is for a static asset (a css file for example) or dynamic one (something served up by the Django App, like answering if Tatis Jr. has an error today).

If the request is static, then Nginx just gets the static data and server it. If it’s dynamic data it hands off the request to Gunicorn which then interacts with the Django App.

So, what actually handles the HTTP request? From the serverfault.com answer above:

[T]he simple answer is Gunicorn. The complete answer is both Nginx and Gunicorn handle the request. Basically, Nginx will receive the request and if it's a dynamic request (generally based on URL patterns) then it will give that request to Gunicorn, which will process it, and then return a response to Nginx which then forwards the response back to the original client.

In my head, I thought that Nginx was ONLY there to handle the static requests (and it is) but I wasn’t clean on how dynamic requests were handled ... but drawing this out really made me stop and ask, “Wait, how DOES that actually work?”

Now I know, and hopefully you do to!

Notes:

These diagrams are generated using the amazing library Diagrams. The code used to generate them is here.

Enhancements: Using GitHub Actions to Deploy

Integrating a version control system into your development cycle is just kind of one of those things that you do, right? I use GutHub for my version control, and it’s GitHub Actions to help with my deployment process.

There are 3 yaml files I have to get my local code deployed to my production server:

- django.yaml

- dev.yaml

- prod.yaml

Each one serving it’s own purpose

django.yaml

The django.yaml file is used to run my tests and other actions on a GitHub runner. It does this in 9 distinct steps and one Postgres service.

The steps are:

- Set up Python 3.8 - setting up Python 3.8 on the docker image provided by GitHub

- psycopg2 prerequisites - setting up

psycopg2to use the Postgres service created - graphviz prerequisites - setting up the requirements for graphviz which creates an image of the relationships between the various models

- Install dependencies - installs all of my Python package requirements via pip

- Run migrations - runs the migrations for the Django App

- Load Fixtures - loads data into the database

- Lint - runs

blackon my code - Flake8 - runs

flake8on my code - Run Tests - runs all of the tests to ensure they pass

name: Django CI

on:

push:

branches-ignore:

- main

- dev

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-18.04

services:

postgres:

image: postgres:12.2

env:

POSTGRES_USER: postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: postgres

POSTGRES_DB: github_actions

ports:

- 5432:5432

# needed because the postgres container does not provide a healthcheck

options: --health-cmd pg_isready --health-interval 10s --health-timeout 5s --health-retries 5

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v1

- name: Set up Python 3.8

uses: actions/setup-python@v1

with:

python-version: 3.8

- uses: actions/cache@v1

with:

path: ~/.cache/pip

key: ${{ runner.os }}-pip-${{ hashFiles('**/requirements.txt') }}

restore-keys: |

${{ runner.os }}-pip-

- name: psycopg2 prerequisites

run: sudo apt-get install python-dev libpq-dev

- name: graphviz prerequisites

run: sudo apt-get install graphviz libgraphviz-dev pkg-config

- name: Install dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install --upgrade pip

pip install psycopg2

pip install -r requirements/local.txt

- name: Run migrations

run: python manage.py migrate

- name: Load Fixtures

run: |

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/User.json

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/Sport.json

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/League.json

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/Conference.json

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/Division.json

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/Venue.json

python manage.py loaddata fixtures/Team.json

- name: Lint

run: black . --check

- name: Flake8

uses: cclauss/GitHub-Action-for-Flake8@v0.5.0

- name: Run tests

run: coverage run -m pytest

dev.yaml

The code here does essentially they same thing that is done in the deploy.sh in my earlier post Automating the Deployment except that it pulls code from my dev branch on GitHub onto the server. The other difference is that this is on my UAT server, not my production server, so if something goes off the rails, I don’t hose production.

name: Dev CI

on:

pull_request:

branches:

- dev

jobs:

deploy:

runs-on: ubuntu-18.04

steps:

- name: deploy code

uses: appleboy/ssh-action@v0.1.2

with:

host: ${{ secrets.SSH_HOST_TEST }}

key: ${{ secrets.SSH_KEY_TEST }}

username: ${{ secrets.SSH_USERNAME }}

script: |

rm -rf StadiaTracker

git clone --branch dev git@github.com:ryancheley/StadiaTracker.git

source /home/stadiatracker/venv/bin/activate

cd /home/stadiatracker/

rm -rf /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker

cp -r /root/StadiaTracker/ /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker

cp /home/stadiatracker/.env /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/StadiaTracker/.env

pip -q install -r /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/requirements.txt

python /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/manage.py migrate

mkdir /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/static

mkdir /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/staticfiles

python /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/manage.py collectstatic --noinput -v0

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart stadiatracker

prod.yaml

Again, the code here does essentially they same thing that is done in the deploy.sh in my earlier post Automating the Deployment except that it pulls code from my main branch on GitHub onto the server.

name: Prod CI

on:

pull_request:

branches:

- main

jobs:

deploy:

runs-on: ubuntu-18.04

steps:

- name: deploy code

uses: appleboy/ssh-action@v0.1.2

with:

host: ${{ secrets.SSH_HOST }}

key: ${{ secrets.SSH_KEY }}

username: ${{ secrets.SSH_USERNAME }}

script: |

rm -rf StadiaTracker

git clone git@github.com:ryancheley/StadiaTracker.git

source /home/stadiatracker/venv/bin/activate

cd /home/stadiatracker/

rm -rf /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker

cp -r /root/StadiaTracker/ /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker

cp /home/stadiatracker/.env /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/StadiaTracker/.env

pip -q install -r /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/requirements.txt

python /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/manage.py migrate

mkdir /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/static

mkdir /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/staticfiles

python /home/stadiatracker/StadiaTracker/manage.py collectstatic --noinput -v0

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart stadiatracker

The general workflow is:

- Create a branch on my local computer with

git switch -c branch_name - Push the code changes to GitHub which kicks off the

django.yamlworkflow. - If everything passes then I do a pull request from

branch_nameintodev. - This kicks off the

dev.yamlworkflow which will update UAT - I check UAT to make sure that everything works like I expect it to (it almost always does … and when it doesn’t it’s because I’ve mucked around with a server configuration which is the problem, not my code)

- I do a pull request from

devtomainwhich updates my production server

My next enhancement is to kick off the dev.yaml process if the tests from django.yaml all pass, i.e. do an auto merge from branch_name to dev, but I haven’t done that yet.

Setting up multiple Django Sites on a Digital Ocean server

If you want to have more than 1 Django site on a single server, you can. It’s not too hard, and using the Digital Ocean tutorial as a starting point, you can get there.

Using this tutorial as a start, we set up so that there are multiple Django sites being served by gunicorn and nginx.

Creating systemd Socket and Service Files for Gunicorn

The first thing to do is to set up 2 Django sites on your server. You’ll want to follow the tutorial referenced above and just repeat for each.

Start by creating and opening two systemd socket file for Gunicorn with sudo privileges:

Site 1

sudo vim /etc/systemd/system/site1.socket

Site 2

sudo vim /etc/systemd/system/site2.socket

The contents of the files will look like this:

[Unit]

Description=siteX socket

[Socket]

ListenStream=/run/siteX.sock

[Install]

WantedBy=sockets.target

Where siteX is the site you want to server from that socket

Next, create and open a systemd service file for Gunicorn with sudo privileges in your text editor. The service filename should match the socket filename with the exception of the extension

sudo vim /etc/systemd/system/siteX.service

The contents of the file will look like this:

[Unit]

Description=gunicorn daemon

Requires=siteX.socket

After=network.target

[Service]

User=sammy

Group=www-data

WorkingDirectory=path/to/directory

ExecStart=path/to/gunicorn/directory

--access-logfile -

--workers 3

--bind unix:/run/gunicorn.sock

myproject.wsgi:application

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Again siteX is the socket you want to serve

Follow tutorial for testing Gunicorn

Nginx

server {

listen 80;

server_name server_domain_or_IP;

location = /favicon.ico { access_log off; log_not_found off; }

location /static/ {

root /path/to/project;

}

location / {

include proxy_params;

proxy_pass http://unix:/run/siteX.sock;

}

}

Again siteX is the socket you want to serve

Next, link to enabled sites

Test Nginx

Open firewall

Should now be able to see sites at domain names

Using PostgreSQL

Once you’ve deployed your code to a web server, you’ll be pretty stoked. I know I was. One thing you’ll need to start thinking about though is converting your SQLite database to a ‘real’ database. I say ‘real’ because SQLite is a great engine to start off with, but once you have more than 1 user, you’ll really need to have a database that can support concurrency, and can scale when you need it to.

Enter PostgreSQL. Django offers built-in database support for several different databases, but Postgres is the preferred engine.

We’ll take care of this in stages:

- Create the database

- Prep project for use of Postgres

- Install needed package

- Update

settings.pyto change to Postgres - Run the migration locally

- Deploy updates to server

- Script it all out

Create the database

I’m going to assume that you already have Postgres installed locally. If you don’t, there are many good tutorials to walk you through it.

You’ll need three things to create a database in Postgres

- Database name

- Database user

- Database password for your user

For this example, I’ll be as generic as possible and choose the following:

- Database name will be

my_database - Database user will be

my_database_user - Database password will be

my_database_user_password

From our terminal we’ll run a couple of commands:

# This will open the Postgres Shell

psql

# From the psql shell

CREATE DATABASE my_database;

CREATE USER my_database_user WITH PASSWORD 'my_database_user_password';

ALTER ROLE my_database_user SET client_encoding TO 'utf8';

ALTER ROLE my_database_user SET default_transaction_isolation TO 'read committed';

ALTER ROLE my_database_user SET timezone TO 'UTC'

The last 3 ALTER commands are based on Django recommendations for Postgres user.

One thing to note, before you go creating databases and users, you should make sure that they don’t already exist. The \l will list the various databases present. If this is your first time in the psql shell you’ll see three databases list:

postgres

template0

template1

To see a list of the users \du will display that. If this is your first time in the psql shell you’ll see one user listed:

postgres

OK … the database has been created. Next, we start updating our project to use this new database engine

Prep project for use of Postgres

Install Needed Package

The only python package needed to use Postgres is psycopg2-binary so we’ll

pip install psycopg2-binary

Update settings.py

The DATABASES portion of the settings.py is set to use SQLite by default and will look (something) like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3',

'NAME': 'mydatabase',

}

}

The Django documentation is really good on what changes need to be made. From the documentation we see that we need to update the DATABASES section to be something like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.postgresql',

'NAME': 'mydatabase',

'USER': 'mydatabaseuser',

'PASSWORD': 'mypassword',

'HOST': '127.0.0.1',

'PORT': '5432',

}

}

With our database from above, ours will look like this:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.postgresql',

'NAME': 'my_database',

'USER': 'my_database_user',

'PASSWORD': 'my_database_user_password',

'HOST': 'localhost',

'PORT': '',

}

}

The HOST is changed to localhost and we remove the value for PORT

Once we get ready to push this to our web server we’ll want to replace the NAME, USER, and PASSWORD with environment variables, but we’ll get to that later

Run migrations

OK, we’ve got our database set up, we’ve got our settings updated to use the new database, now we can run set that database up.

All that we need to do is to:

python manage.py migrate

This will run any migrations that we had created previously on our new Postgres database.

A few things to note:

- You will need to create a new

superuser - You will need to migrate over any data from the old SQLite database1

Congratulations! You’ve migrated from SQLite to Postgres!

- This can be done with the

datadumpanddataloadcommands available inmanage.py↩︎

Automating the deployment

We got everything set up, and now we want to automate the deployment.

Why would we want to do this you ask? Let’s say that you’ve decided that you need to set up a test version of your site (what some might call UAT) on a new server (at some point I’ll write something up about about multiple Django Sites on the same server and part of this will still apply then). How can you do it?

Well you’ll want to write yourself some scripts!

I have a mix of Python and Shell scripts set up to do this. They are a bit piece meal, but they also allow me to run specific parts of the process without having to try and execute a script with ‘commented’ out pieces.

Python Scripts

create_server.py

destroy_droplet.py

Shell Scripts

copy_for_deploy.sh

create_db.sh

create_server.sh

deploy.sh

deploy_env_variables.sh

install-code.sh

setup-server.sh

setup_nginx.sh

setup_ssl.sh

super.sh

upload-code.sh

The Python script create_server.py looks like this:

# create_server.py

import requests

import os

from collections import namedtuple

from operator import attrgetter

from time import sleep

Server = namedtuple('Server', 'created ip_address name')

doat = os.environ['DIGITAL_OCEAN_ACCESS_TOKEN']

# Create Droplet

headers = {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

'Authorization': f'Bearer {doat}',

}

data = <data_keys>

print('>>> Creating Server')

requests.post('https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets', headers=headers, data=data)

print('>>> Server Created')

print('>>> Waiting for Server Stand up')

sleep(90)

print('>>> Getting Droplet Data')

params = (

('page', '1'),

('per_page', '10'),

)

get_droplets = requests.get('https://api.digitalocean.com/v2/droplets', headers=headers, params=params)

server_list = []

for d in get_droplets.json()['droplets']:

server_list.append(Server(d['created_at'], d['networks']['v4'][0]['ip_address'], d['name']))

server_list = sorted(server_list, key=attrgetter('created'), reverse=True)

server_ip_address = server_list[0].ip_address

db_name = os.environ['DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME']

db_username = os.environ['DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME']

if server_ip_address != <production_server_id>:

print('>>> Run server setup')

os.system(f'./setup-server.sh {server_ip_address} {db_name} {db_username}')

print(f'>>> Server setup complete. You need to add {server_ip_address} to the ALLOWED_HOSTS section of your settings.py file ')

else:

print('WARNING: Running Server set up will destroy your current production server. Aborting process')

Earlier I said that I liked Digital Ocean because of it’s nice API for interacting with it’s servers (i.e. Droplets). Here we start to see some.

The First part of the script uses my Digital Ocean Token and some input parameters to create a Droplet via the Command Line. The sleep(90) allows the process to complete before I try and get the IP address. Ninety seconds is a bit longer than is needed, but I figure, better safe than sorry … I’m sure that there’s a way to call to DO and ask if the just created droplet has an IP address, but I haven’t figured it out yet.

After we create the droplet AND is has an IP address, we get it to pass to the bash script server-setup.sh.

# server-setup.sh

#!/bin/bash

# Create the server on Digital Ocean

export SERVER=$1

# Take secret key as 2nd argument

if [[ -z "$1" ]]

then

echo "ERROR: No value set for server ip address1"

exit 1

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Setting up $SERVER"

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Updating apt sources"

apt-get -qq update

echo -e "\n>>> Upgrading apt packages"

apt-get -qq upgrade

echo -e "\n>>> Installing apt packages"

apt-get -qq install python3 python3-pip python3-venv tree supervisor postgresql postgresql-contrib nginx

echo -e "\n>>> Create User to Run Web App"

if getent passwd burningfiddle

then

echo ">>> User already present"

else

adduser --disabled-password --gecos "" burningfiddle

echo -e "\n>>> Add newly created user to www-data"

adduser burningfiddle www-data

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Make directory for code to be deployed to"

if [[ ! -d "/home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle" ]]

then

mkdir /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle

else

echo ">>> Skipping Deploy Folder creation - already present"

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Create VirtualEnv in this directory"

if [[ ! -d "/home/burningfiddle/venv" ]]

then

python3 -m venv /home/burningfiddle/venv

else

echo ">>> Skipping virtualenv creation - already present"

fi

# I don't think i need this anymore

echo ">>> Start and Enable gunicorn"

systemctl start gunicorn.socket

systemctl enable gunicorn.socket

EOF

./setup_nginx.sh $SERVER

./deploy_env_variables.sh $SERVER

./deploy.sh $SERVER

All of that stuff we did before, logging into the server and running commands, we’re now doing via a script. What the above does is attempt to keep the server in an idempotent state (that is to say you can run it as many times as you want and you don’t get weird artifacts … if you’re a math nerd you may have heard idempotent in Linear Algebra to describe the multiplication of a matrix by itself and returning the original matrix … same idea here!)

The one thing that is new here is the part

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

...

EOF

A block like that says, “take everything in between EOF and run it on the server I just ssh’d into using bash.

At the end we run 3 shell scripts:

setup_nginx.shdeploy_env_variables.shdeploy.sh

Let’s review these scripts

The script setup_nginx.sh copies several files needed for the nginx service:

gunicorn.servicegunicorn.socketsnginx.conf

It then sets up a link between the available-sites and enabled-sites for nginx and finally restarts nginx

# setup_nginx.sh

export SERVER=$1

export sitename=burningfiddle

scp -r ../config/gunicorn.service root@$SERVER:/etc/systemd/system/

scp -r ../config/gunicorn.socket root@$SERVER:/etc/systemd/system/

scp -r ../config/nginx.conf root@$SERVER:/etc/nginx/sites-available/$sitename

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

echo -e ">>> Set up site to be linked in Nginx"

ln -s /etc/nginx/sites-available/$sitename /etc/nginx/sites-enabled

echo -e ">>> Restart Nginx"

systemctl restart nginx

echo -e ">>> Allow Nginx Full access"

ufw allow 'Nginx Full'

EOF

The script deploy_env_variables.sh copies environment variables. There are packages (and other methods) that help to manage environment variables better than this, and that is one of the enhancements I’ll be looking at.

This script captures the values of various environment variables (one at a time) and then passes them through to the server. It then checks to see if these environment variables exist on the server and will place them in the /etc/environment file

export SERVER=$1

DJANGO_SECRET_KEY=printenv | grep DJANGO_SECRET_KEY

DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD=printenv | grep DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD

DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME=printenv | grep DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME

DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME=printenv | grep DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME

DJANGO_SUPERUSER_PASSWORD=printenv | grep DJANGO_SUPERUSER_PASSWORD

DJANGO_DEBUG=False

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

if [[ "\$DJANGO_SECRET_KEY" != "$DJANGO_SECRET_KEY" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_SECRET_KEY=$DJANGO_SECRET_KEY" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_SECRET_KEY - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD" != "$DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD=$DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_PG_PASSWORD - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME" != "$DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME=$DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_PG_USER_NAME - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME" != "$DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME=$DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_PG_DB_NAME - already present"

fi

if [[ "\$DJANGO_DEBUG" != "$DJANGO_DEBUG" ]]

then

echo "DJANGO_DEBUG=$DJANGO_DEBUG" >> /etc/environment

else

echo ">>> Skipping DJANGO_DEBUG - already present"

fi

EOF

The deploy.sh calls two scripts itself:

# deploy.sh

#!/bin/bash

set -e

# Deploy Django project.

export SERVER=$1

#./scripts/backup-database.sh

./upload-code.sh

./install-code.sh

The final two scripts!

The upload-code.sh script uploads the files to the deploy folder of the server while the install-code.sh script move all of the files to where then need to be on the server and restart any services.

# upload-code.sh

#!/bin/bash

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Copying Django project files to server."

if [[ -z "$SERVER" ]]

then

echo "ERROR: No value set for SERVER."

exit 1

fi

echo -e "\n>>> Preparing scripts locally."

rm -rf ../../deploy/*

rsync -rv --exclude 'htmlcov' --exclude 'venv' --exclude '*__pycache__*' --exclude '*staticfiles*' --exclude '*.pyc' ../../BurningFiddle/* ../../deploy

echo -e "\n>>> Copying files to the server."

ssh root@$SERVER "rm -rf /root/deploy/"

scp -r ../../deploy root@$SERVER:/root/

echo -e "\n>>> Finished copying Django project files to server."

And finally,

# install-code.sh

#!/bin/bash

# Install Django app on server.

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Installing Django project on server."

if [[ -z "$SERVER" ]]

then

echo "ERROR: No value set for SERVER."

exit 1

fi

echo $SERVER

ssh root@$SERVER /bin/bash << EOF

set -e

echo -e "\n>>> Activate the Virtual Environment"

source /home/burningfiddle/venv/bin/activate

cd /home/burningfiddle/

echo -e "\n>>> Deleting old files"

rm -rf /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle

echo -e "\n>>> Copying new files"

cp -r /root/deploy/ /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle

echo -e "\n>>> Installing Python packages"

pip install -r /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/requirements.txt

echo -e "\n>>> Running Django migrations"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py migrate

echo -e "\n>>> Creating Superuser"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py createsuperuser --noinput --username bfadmin --email rcheley@gmail.com || true

echo -e "\n>>> Load Initial Data"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py loaddata /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/fixtures/pages.json

echo -e "\n>>> Collecting static files"

python /home/burningfiddle/BurningFiddle/manage.py collectstatic

echo -e "\n>>> Reloading Gunicorn"

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart gunicorn

EOF

echo -e "\n>>> Finished installing Django project on server."

Preparing the code for deployment to Digital Ocean

OK, we’ve got our server ready for our Django App. We set up Gunicorn and Nginx. We created the user which will run our app and set up all of the folders that will be needed.

Now, we work on deploying the code!

Deploying the Code

There are 3 parts for deploying our code:

- Collect Locally

- Copy to Server

- Place in correct directory

Why don’t we just copy to the spot on the server we want o finally be in? Because we’ll need to restart Nginx once we’re fully deployed and it’s easier to have that done in 2 steps than in 1.

Collect the Code Locally

My project is structured such that there is a deploy folder which is on the Same Level as my Django Project Folder. That is to say

We want to clear out any old code. To do this we run from the same level that the Django Project Folder is in

rm -rf deploy/*

This will remove ALL of the files and folders that were present. Next, we want to copy the data from the yoursite folder to the deploy folder:

rsync -rv --exclude 'htmlcov' --exclude 'venv' --exclude '*__pycache__*' --exclude '*staticfiles*' --exclude '*.pyc' yoursite/* deploy

Again, running this form the same folder. I’m using rsync here as it has a really good API for allowing me to exclude items (I’m sure the above could be done better with a mix of Regular Expressions, but this gets the jobs done)

Copy to the Server

We have the files collected, now we need to copy them to the server.

This is done in two steps. Again, we want to remove ALL of the files in the deploy folder on the server (see rationale from above)

ssh root@$SERVER "rm -rf /root/deploy/"

Next, we use scp to secure copy the files to the server

scp -r deploy root@$SERVER:/root/

Our files are now on the server!

Installing the Code

We have several steps to get through in order to install the code. They are:

- Activate the Virtual Environment

- Deleting old files

- Copying new files

- Installing Python packages

- Running Django migrations

- Collecting static files

- Reloading Gunicorn

Before we can do any of this we’ll need to ssh into our server. Once that’s done, we can proceed with the steps below.

Above we created our virtual environment in a folder called venv located in /home/yoursite/. We’ll want to activate it now (1)

source /home/yoursite/venv/bin/activate

Next, we change directory into the yoursite home directory

cd /home/yoursite/

Now, we delete the old files from the last install (2):

rm -rf /home/yoursite/yoursite

Copy our new files (3)

cp -r /root/deploy/ /home/yoursite/yoursite

Install our Python packages (4)

pip install -r /home/yoursite/yoursite/requirements.txt

Run any migrations (5)

python /home/yoursite/yoursite/manage.py migrate

Collect Static Files (6)

python /home/yoursite/yoursite/manage.py collectstatic

Finally, reload Gunicorn

systemctl daemon-reload

systemctl restart gunicorn

When we visit our domain we should see our Django Site fn

Page 4 / 13